Understanding health workforce roles in pediatric type 1 diabetes care: findings from a global survey

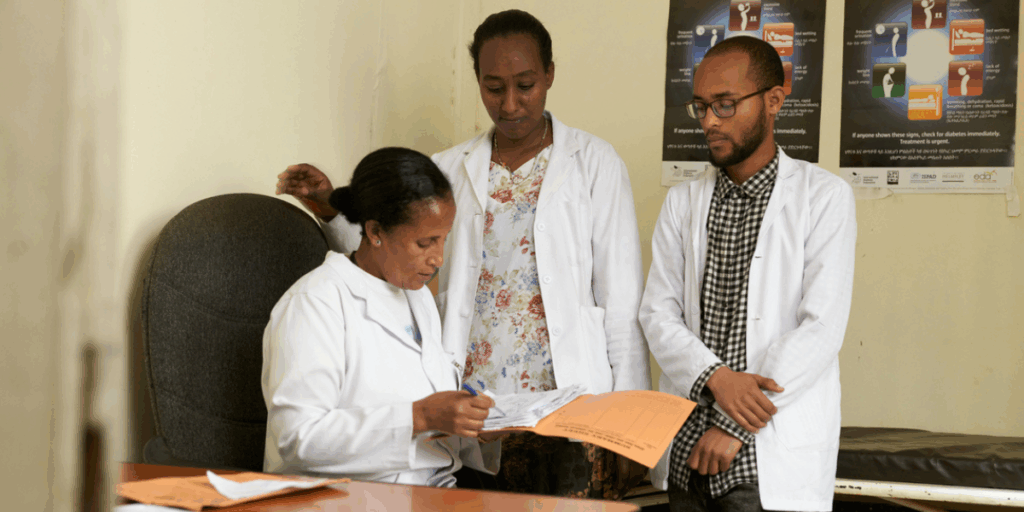

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology has published new research, led by Life for a Child and ISPAD, examining how clinical tasks for pediatric type 1 diabetes are distributed across healthcare professionals worldwide. Despite long-standing recognition that multidisciplinary teams support better outcomes, many health systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, continue to rely heavily on doctors as the primary providers of diabetes care for children and adolescents.

Our study provides new evidence by analysing responses from a broad group of healthcare professionals across diverse settings. The findings highlight the predominance of doctor-centred care but also demonstrate considerable openness to more distributed models involving nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, and trained peer supporters.

What the survey shows

Respondents represented a mix of doctors, nurses, and allied healthcare professionals across government, NGO, and private facilities. In most countries, core T1D tasks remained concentrated among doctors: reviewing glucose logbooks, adjusting insulin regimens, ordering or interpreting tests, and writing prescriptions. Nurses and allied healthcare professionals were less frequently responsible for these elements, even where they formed a substantial part of the diabetes workforce.

At the same time, there were exceptions. Several countries, across different income levels, reported shared roles in follow-up diabetes education, insulin technique support, and day-to-day management. Lay diabetes educators were part of multidisciplinary teams in more than half of LMIC settings represented, primarily contributing to education and psychosocial support.

Attitudes toward change were strikingly positive. Many respondents, including doctors, indicated that specific tasks could appropriately be shifted or shared with other trained members of the health team. These included reviewing glucose data, providing education at diagnosis and follow-up, advising on insulin adjustments, and in some settings prescribing insulin. Comments highlighted practical considerations: rising caseloads, geographic reach, and the ability of trained nurses to provide consistent, family-centred support.

Where challenges persist

Alongside this willingness to share tasks, respondents noted structural barriers. These included limited training opportunities for nurses and allied healthcare professionals, absence of formal diabetes specialisation pathways, regulatory restrictions on prescribing or conducting certain activities, and high staff turnover that undermines continuity.

Some responses reflected longstanding norms that position diabetes care as exclusively doctor-led, even where workforce pressures suggest the need for more flexible approaches. These insights echo broader global healthcare experience across HIV, maternal health, and chronic disease programmes, where carefully supported task-shifting has been shown to maintain or improve quality of care.

Implications for future work

Although exploratory, the survey suggests that clearer national frameworks and regulatory support could help health systems make more effective use of their available workforce. Emerging training programmes, such as the IDF School of Diabetes, ADECA, and PEDAF, will be important in strengthening skills, but respondents’ accounts underline that training must be accompanied by accreditation mechanisms, supervision structures, and institutional recognition.

Future research could examine how individual countries adapt these approaches, and how changes in task allocation contribute to measurable improvements in glycaemic outcomes, service coverage, and continuity of care. This study provides a baseline understanding of current practice and highlights areas for further investigation and policy development.

Closing reflection

The survey reveals substantial variation in how pediatric type 1 diabetes care is delivered globally. While many systems remain heavily doctor-centric, there is readiness among clinicians to adopt more distributed models of care.

As countries respond to growing diabetes caseloads alongside broader workforce constraints, understanding and supporting appropriate task-shifting and task-sharing strategies will be central to strengthening sustainable, high-quality care for children and young people living with type 1 diabetes.

View the full article: The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Acknowledgment

The study was conducted in collaboration with colleagues from the International Society for Pediatric & Adolescent Diabetes, Santé Diabète (Mali), Geneva University Hospitals (Switzerland), Shree Hindu Mandal Hospital (Tanzania), Uganda Martyrs University and St Francis Hospital (Uganda), BADAS/BIRDEM (Bangladesh), the University of Luxembourg, and the University of the Sunshine Coast (Australia).

We are grateful to the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes for their partnership in disseminating the survey, and to the 260 clinicians from 83 countries who generously contributed their time and experience.